In a world where travel has become increasingly rushed and surface-level, New Zealand presents something different. At this destination, architectural heritage, cultural authenticity, and luxury come together in remarkable harmony. This isn’t the New Zealand of hurried bus tours and checkbox experiences. On the contrary, New Zealand can be a place where time seems to slow down, where every building has a story to tell, and where the journey becomes just as meaningful as the destination itself. Aroha Luxury New Zealand Tours works hard to curate the perfect tour for you, so if this sounds like something you’d like to experience, get in touch!

- The sacred architecture of Māori culture

- Colonial grandeur and European influences

- Contemporary innovation: Modern architecture with soul

- Everything you need to plan your trip in 2025

- The Arts and Crafts Renaissance

- Wine country architecture

- Luxury accommodation meets architectural excellence

- Slow luxury travel

The sacred architecture of Māori culture

New Zealand’s architectural landscape tells the story of cultural evolution like a living book. The country’s built environment reflects waves of influence that have shaped its identity over centuries, starting with the ingenious constructions of the Māori people.

Traditional Māori architecture, think marae complexes and their intricately carved meeting houses, represents far more than just shelter. These structures embody spiritual beliefs, genealogical histories, and community values all rolled into one. The meeting house, or whare tupuna, literally represents an ancestor. Its ridgepole becomes the backbone, its rafters the ribs, and its facade the face of a tribal forbear. For travellers seeking more profound experiences, spending time in these sacred spaces while observing proper cultural protocols offers profound insights into New Zealand’s Indigenous worldview. It’s about understanding, not just observing.

Colonial grandeur and European influences

European settlers arrived in New Zealand in the 19th century, introducing entirely new architectural vocabularies that catalysed a dialogue between imported styles and local conditions. Colonial Georgian architecture found fresh expression in timber rather than stone, while Victorian Gothic Revival churches and public buildings showed ambitious attempts to recreate European grandeur in this antipodean setting.

Towns like Oamaru showcase this period beautifully. Its Victorian Precinct, constructed from locally quarried limestone, earned the town its nickname “The Whitestone City.” Here, luxury travellers can stay in beautifully restored heritage accommodations where original architectural features have been carefully preserved while modern amenities ensure contemporary comfort.

Contemporary innovation: Modern architecture with soul

Modern New Zealand architecture has gained international recognition for its innovative response to landscape and climate. The country’s architects have developed a distinctive approach that honours both European architectural traditions and Indigenous sensibilities. Travellers interested in architectural pilgrimage will find New Zealand’s cities and countryside dotted with award-winning contemporary buildings that push boundaries while respecting context.

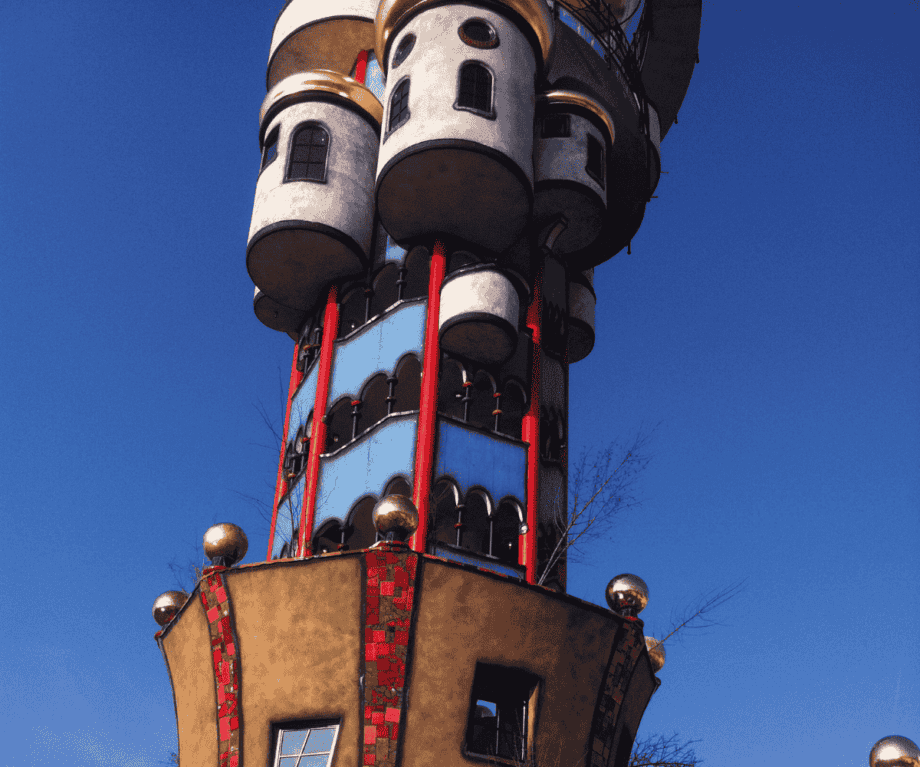

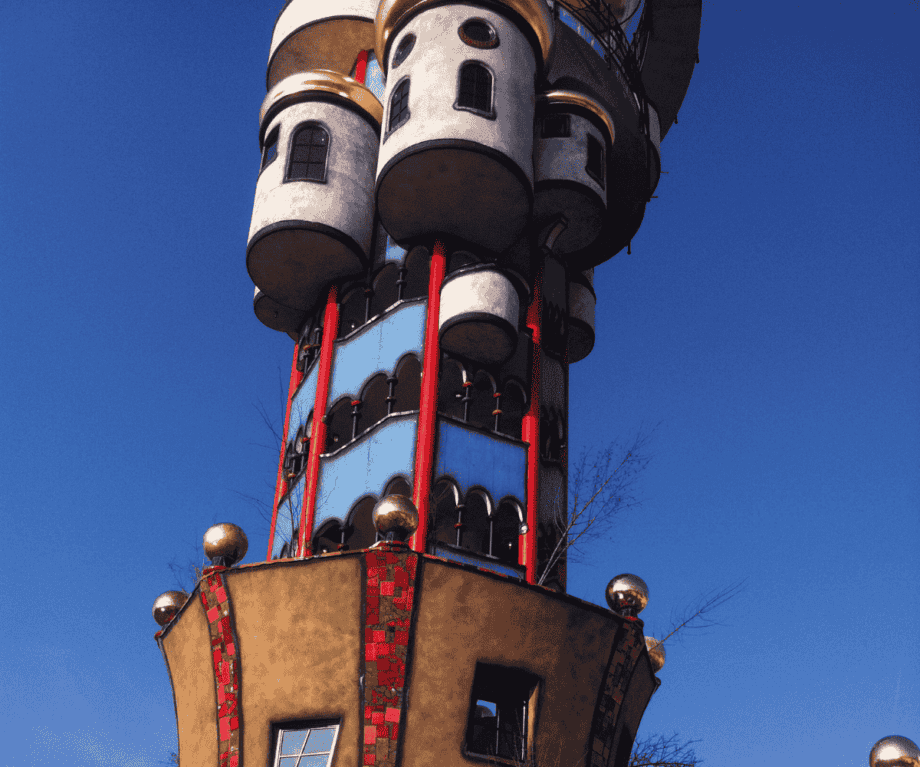

Friedensreich Hundertwasser

Perhaps no architect has left a more distinctive mark on New Zealand’s architectural makeup than Friedensreich Hundertwasser, the Austrian-born artist who made New Zealand his home. Hundertwasser was staging a revolution against what he saw as the dehumanising effects of modern architecture. His approach was radical and deeply human, believing that straight lines were “godless and immoral,” that geometric precision was killing the soul of our cities, and that “houses are the third skin of man.” The Hundertwasser Toilet in Kawakawa stands as his most famous New Zealand work, transforming a mundane public facility into a work of art. However, his influence extends far beyond this single building; his ideas about reintegrating nature into rooftops and allowing buildings to grow organically rather than conforming to grid systems continue to influence New Zealand architects today.

Collective architectural vision

While individual visionaries like Hundertwasser helped shape New Zealand’s architectural philosophy, entire towns sometimes reinvented themselves through collective architectural vision. Napier could be considered one of the most dramatic examples of this phenomenon. After a devastating 1931 earthquake destroyed the town and killed 256 people, Napier rebuilt itself almost entirely in Art Deco style, creating what is now recognised as the highest concentration of Art Deco buildings in the world. The reconstruction involved creating earthquake-safe, two-story reinforced concrete structures that ideally suited Art Deco’s angular, streamlined aesthetic. The result is a compact town centre where entire blocks showcase the optimism and modernist vision of the 1930s, complete with geometric facades that sometimes incorporate Māori motifs, creating a unique mix of international style and local identity.

A Gothic revival masterpiece

Wellington’s Old St Paul’s represents another facet of New Zealand’s architectural heritage, the Gothic Revival masterpiece that demonstrates how European ecclesiastical traditions could be reimagined using native materials. Constructed between 1865 and 1866 entirely from native timbers, Old St. Paul’s is an excellent showcase of Gothic Revival architecture. The interior of the building becomes a glorious riot of colour and light, with acoustics that make every whisper resonate through the timber structure. Old St. Paul’s has evolved into a non-denominational sanctuary where architecture serves as both a spiritual space and a cultural venue, hosting a range of events from concerts to corporate gatherings while maintaining its sacred atmosphere.

The cultural influence of New Zealand’s architectural heritage extends far beyond the buildings themselves. New Zealand’s approach to prioritising environmental preservation, innovation, indigenous and colonial architectural traditions offers lessons for travellers and professionals alike. Travellers who take the time to understand these buildings gain insights into New Zealand’s cultural values, ecological consciousness, and innovative spirit. It’s about seeing the bigger picture of how architecture reflects and shapes the society that creates it.

Everything you need to plan your trip in 2025

The Arts and Crafts Renaissance

The Arts and Crafts movement found particularly fertile ground in New Zealand, producing some of the country’s most beloved architectural works. The movement’s emphasis on local materials, craftsmanship, and harmony with the landscape resonated with New Zealand’s emerging sense of place.

Architects like Sir Basil Hooper and James Chapman-Taylor created buildings that were unmistakably of their time yet deeply rooted in their environment. Travellers seeking authentic experiences might find themselves staying in carefully restored Arts and Crafts homes, now serving as boutique accommodations where every detail, from the leadlight windows to the native timber panelling, speaks to a philosophy of beauty born from utility and place.

Wine country architecture

New Zealand’s wine regions offer especially compelling examples of how architecture, landscape, and cultural values intersect. The wineries of Central Otago, Marlborough, and Hawke’s Bay have commissioned architects to create buildings that are simultaneously functional, beautiful, and expressive of their topography.

These structures often incorporate sustainable technologies, native materials, and design principles that blur the boundaries between interior and exterior spaces. Travellers can spend entire days at these properties, experiencing how architecture enhances the sensory pleasures of wine tasting while deepening appreciation for the landscape that produces these exceptional wines.

Luxury accommodation meets architectural excellence

Modern luxury accommodations in New Zealand increasingly recognise that architecture itself can be the primary attraction. Properties like Eichardt’s Private Hotel in Queenstown, the Lindis in Ahuriri Valley and Kinloch Manor and Villas seamlessly blend international luxury standards with the distinctive character of New Zealand architecture.

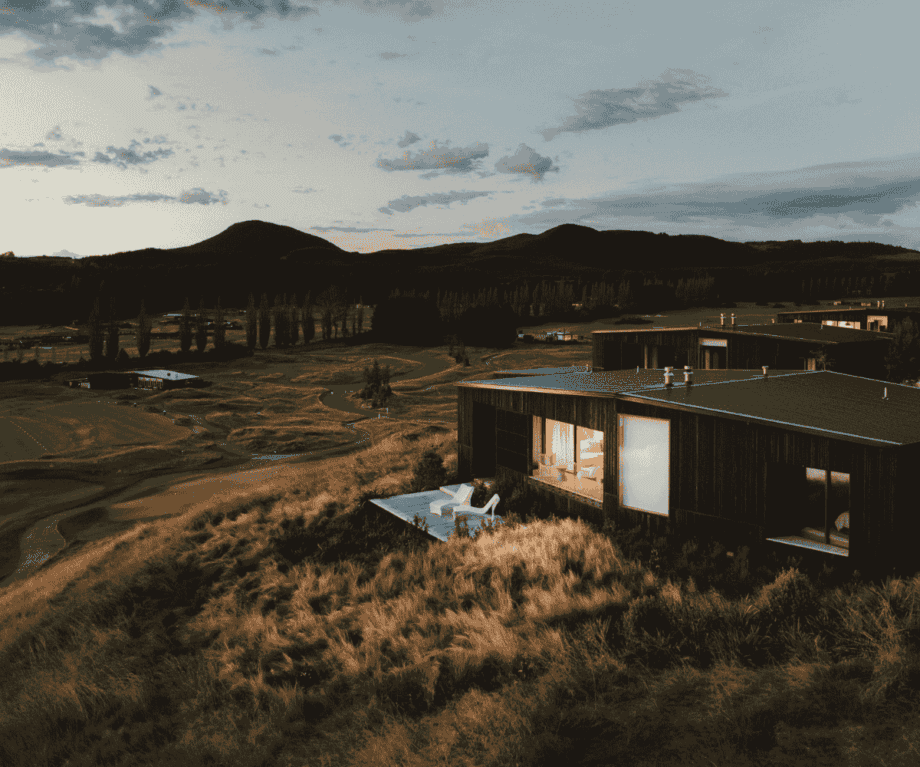

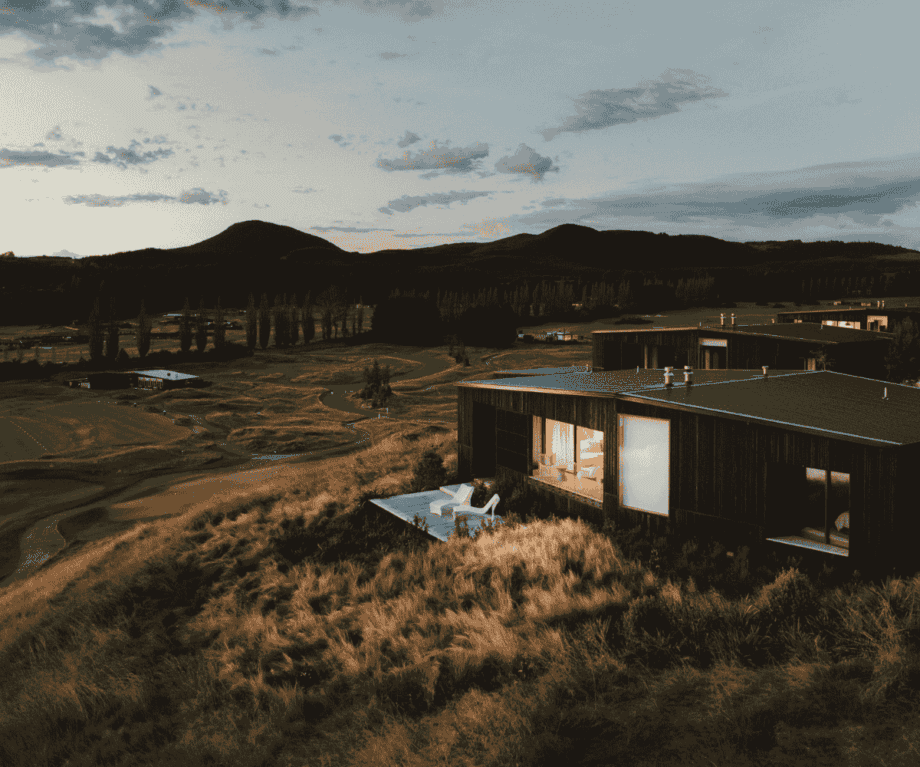

The Lindis

The Lindis, located in New Zealand’s remote Ahuriri Valley, perfectly captures how Kiwi architecture can work with rather than against the landscape. This luxury lodge doesn’t try to dominate the dramatic glacial terrain; instead, it becomes part of it. The main building sits low and follows the natural contours of the ancient moraine, while the real stars are the innovative glass pods scattered across the property.

These clever little retreats feature mirrored glass on three sides, so during the day, they practically blend into the surroundings, reflecting the mountains, tussock grasslands, and ever-changing light. From inside, guests enjoy an almost boundless connection to the landscape through floor-to-ceiling windows, while the heated outdoor tubs allow you to soak in the beauty of the Southern Alps. It’s a brilliant example of how contemporary New Zealand architecture has learnt to celebrate the country’s stunning natural environments rather than compete with them, creating spaces that feel like they’ve grown from the land itself whilst still delivering all the comfort and luxury you’d want from a world-class retreat.

Kinloch Manor and Villas: Winner of New Zealand architecture awards with best commercial architecture & best hospitality and retail

Sitting on 254 hectares of stunning Lake Taupo shoreline, Kinloch Manor is the kind of place that makes you do a double-take; it’s not your typical Kiwi lodge. Award-winning architect Ken Crosson reckons it’s like “a reinterpreted modern-day Scottish Baronial Castle”, and honestly, that’s spot on. This is a proper stone fortress of a building that’s “massive, heavy and powerful”, the sort of construction you just don’t see much of in New Zealand. But here’s the clever bit: instead of trying to blend into the landscape as so many other places do, Kinloch Manor owns its presence and uses that hefty stone structure to perfectly frame those jaw-dropping lake views from pretty much everywhere you look. It’s like the architects said, “Right, we’re going big, but we’re going to make sure every window showcases that incredible Lake Taupo panorama.”

The result is this fascinating clash between old-world castle vibes and quintessentially Kiwi Lake Country. Somehow, it works brilliantly, giving you all the drama of a Scottish manor house but with that uniquely New Zealand backdrop of volcanic peaks and pristine waters.

Eichardt’s Private Hotel

Right on Queenstown’s lakefront, Eichardt’s Private Hotel is a brilliant example of how to give a historic building a modern makeover without losing its soul. This beauty has been welcoming guests since 1861, back when gold rush prospectors were rolling into town, making it one of New Zealand’s oldest continuously operating hotels.

The genius is in how designer Virginia Fisher has blended “antique and contemporary style” so perfectly. You’ve got those gorgeous, textured sandstone walls and chunky, repurposed timbers that tell stories of the gold rush era. Still, Fisher added contemporary touches with “confident strokes and flawless symmetry,” making everything feel fresh and luxurious. The white stone façade might look timeless, but inside, it’s hiding some seriously sophisticated modern luxury, all with those knockout Lake Wakatipu views to boot.

These intentionally designed properties understand that luxury travel is increasingly about unique experiences and authentic connections to place rather than mere opulence divorced from context. The building becomes part of the experience, not just a place to sleep.

Slow luxury travel

Deliberate and slower-paced luxury travel in New Zealand offers travellers a chance to experience a more profound type of holiday, exploring NZ’s architectural gems. Rather than rushing between tourist-filled destinations, thoughtful travellers can spend days in a single location, allowing the built environment to reveal its mysteries gradually.

In Christchurch, the post-earthquake reconstruction has created a laboratory for innovative architecture where visitors can witness a city reimagining itself. Luxury travellers might choose to stay in recently opened boutique hotels that exemplify this new architectural confidence, buildings that rise from the rubble with renewed purpose and beauty.

In New Zealand, where the built environment tells the story of culture, adaptation, and innovation, travel here becomes not just luxurious but transformative. Slow travel is what changes perspectives, deepens understanding, and creates lasting connections to a place.

Did you enjoy this article?

Receive similar content direct to your inbox.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser to submit the form